Places: Eccleston, Lancashire

Widget not in any sidebars

Place Type

Parish

County

Lancashire

Deanery

Leyland

Causes

EDC 5/15/1 – George Wrenhalle contra Lawrence Fynch.

ECCLESTON

Although there was a lengthy dispute in the late thirteenth century about whether Eccleston was a chapelry of Croston, or a parish in its own right, the decision pronounced by the bishop of Coventry and Lichfield in 1317 was that Eccleston was, indeed, a parish. It comprised the townships of Eccleston, Heskin, Parbold and Wrightington and the chapelry of Douglas in Parbold.

The parish was situated to the west of the county, away from the more densely populated areas of Manchester and Preston and has been characterised as one of the ‘most Catholic’ parishes of the county (Haigh, p. 284). Bl. John Finch was born in Eccleston in about 1548. He converted to Catholicism and helped with the underground network of priests, sheltering some in his home. He was arrested and executed at Lancaster in 1584 after refusing to accept the Royal Supremacy.

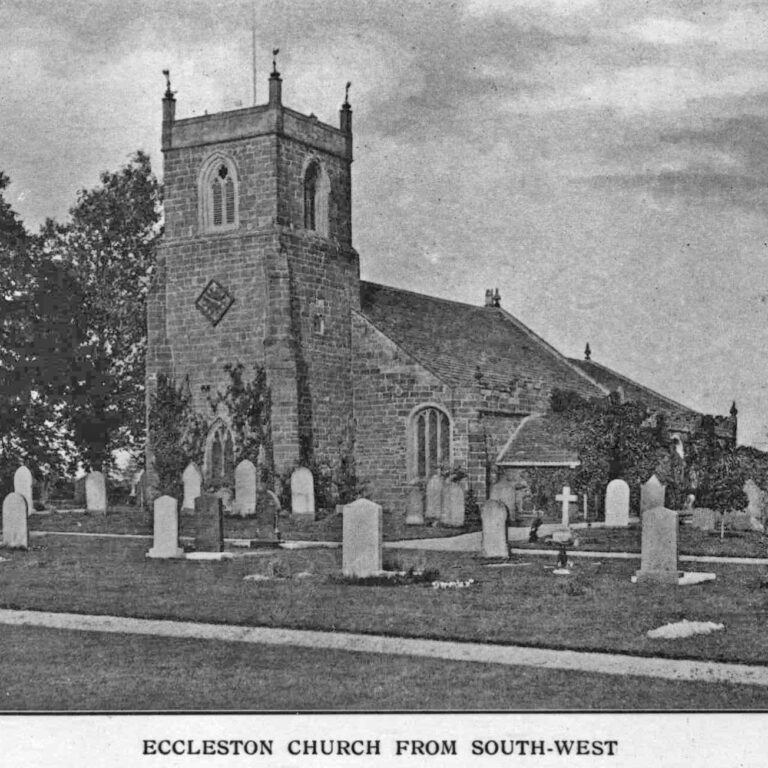

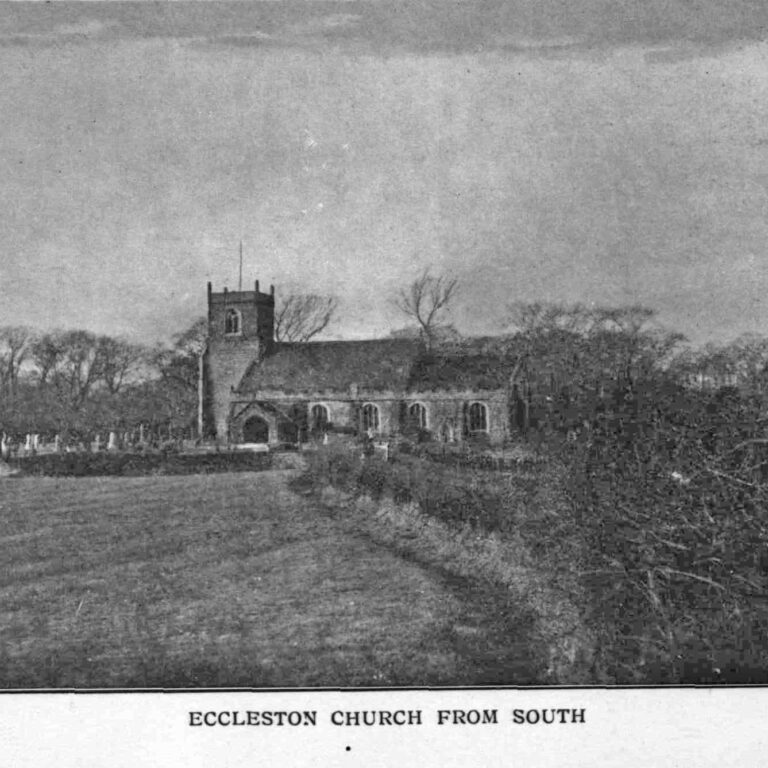

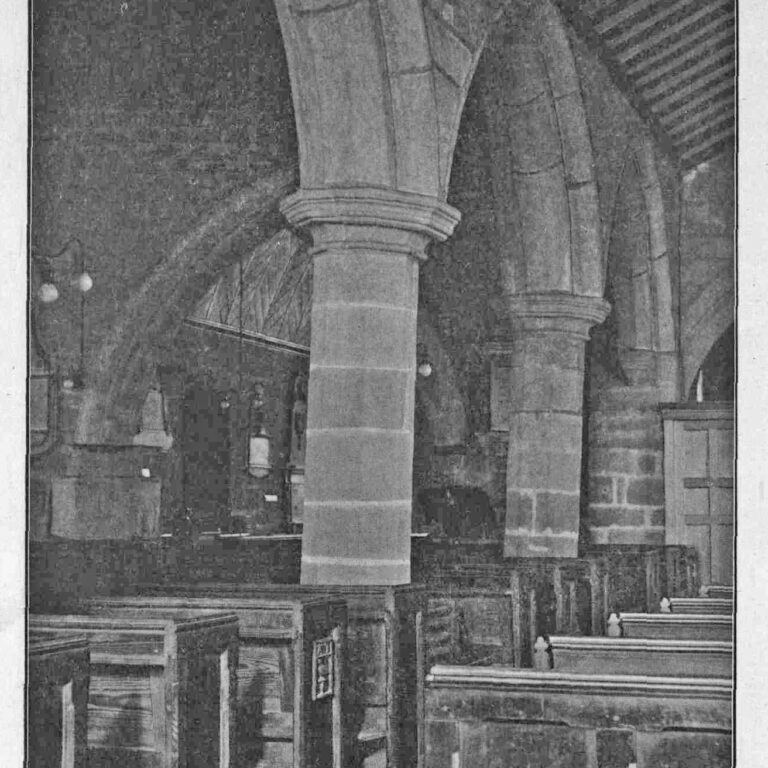

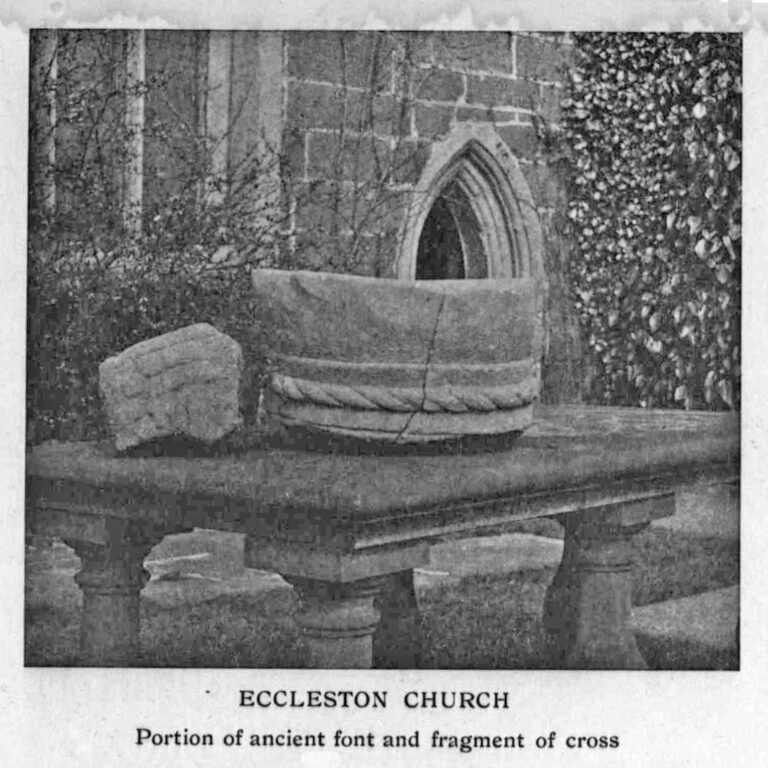

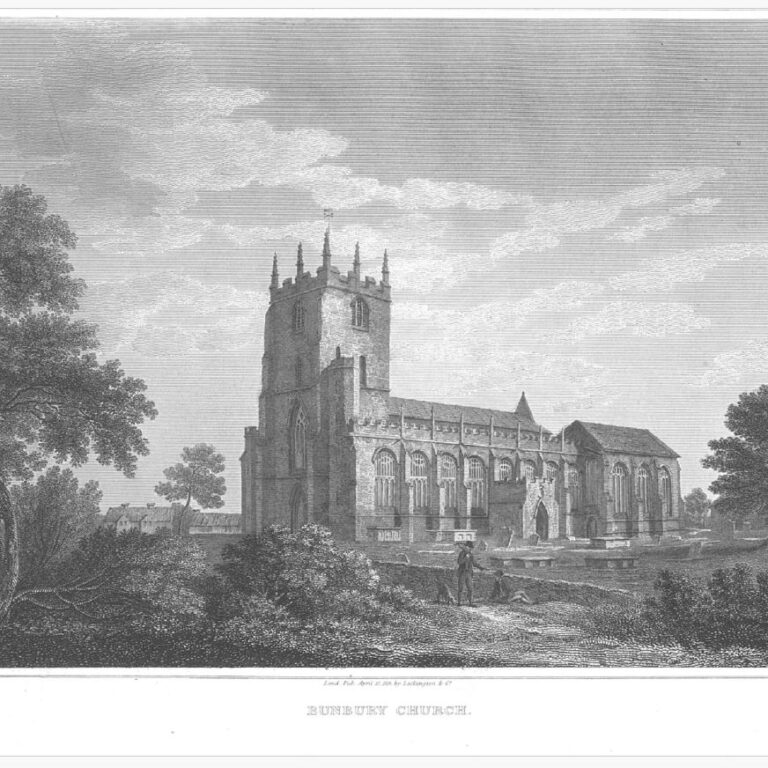

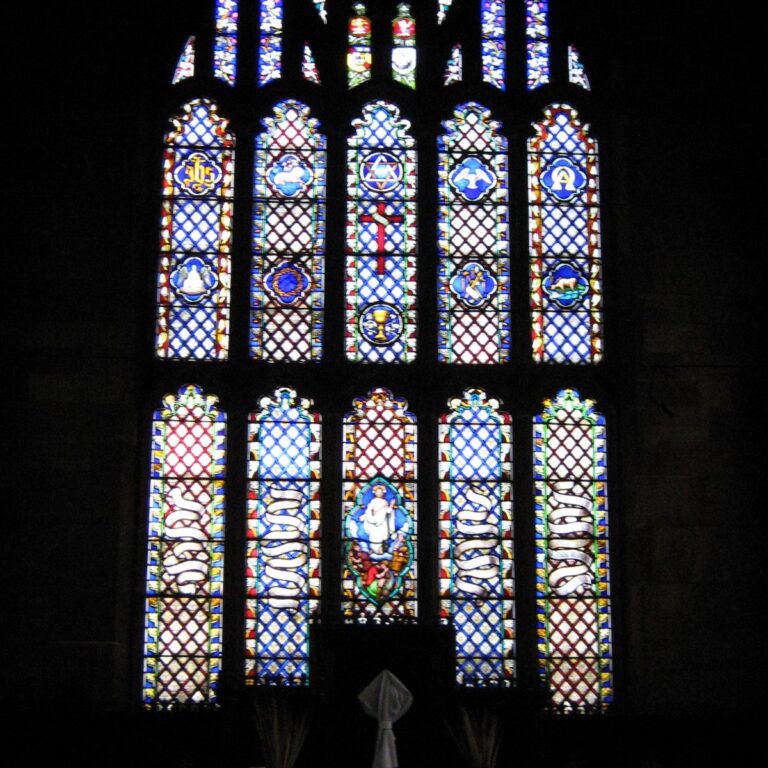

The church is situated in the north of the parish. Part of the fourteenth century church building survives, comprising parts of the chancel and the lower part of the tower.

The building was reconstructed in the 18th century and although the original plan seems to have been to pull down the existing building and rebuild it entirely, this was not done and the churchwardens’ accounts record payments for repairs and rebuilding over the period from 1721 to 1737. It underwent subsequent substantial restoration work in the 19th century. The tower has no staircase and the only access to the belfry is by a ladder.

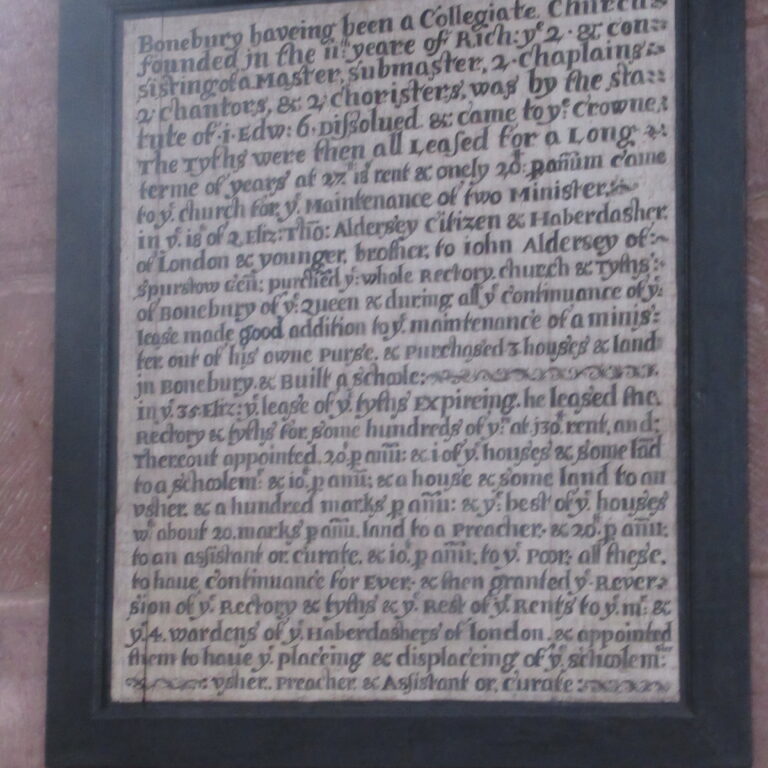

One moiety of the parish was given to the Benedictine Abbey of St Martin of Sées in Normandy shortly after the Norman Conquest and the remainder was given to the priory of Lancaster, a cell of that abbey, some two hundred years later. However, during the long periods of war with France the English monarchs seized some of the assets of alien monasteries so the rectors of Eccleston were often presented by the Crown until, in about 1430, the advowson was granted to Sir Thomas Stanley and so he and his successors, the earls of Derby, presented to the parish until 1596 when they sold it to Thomas Lathom of Parbold.

The parish was often held in plurality and for short periods, many of the rectors being non-resident.

There were coal mines and quarries for building stone in the parish and the cotton industry developed from the middle of the nineteenth century but much of the parish remained agricultural.

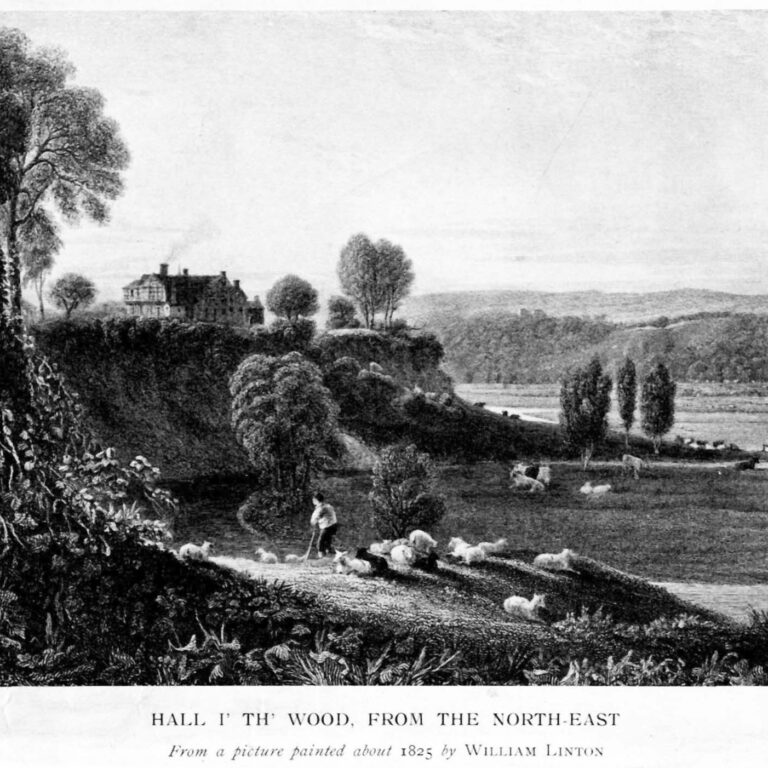

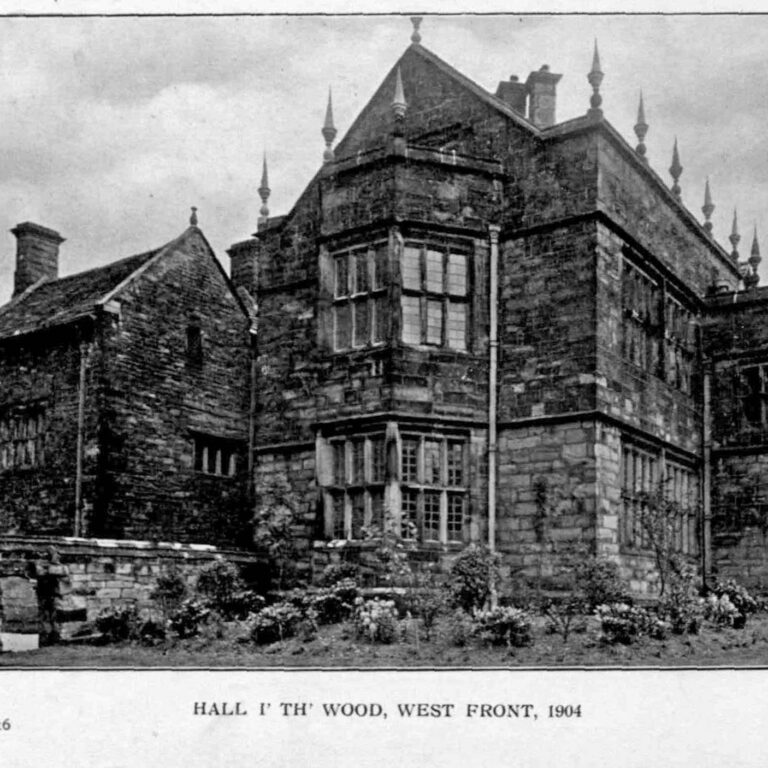

The black and white images are reproduced from volume 63 of the Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire by kind permission of The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire.

Sources:

E. H. Burton and J. H. Pollen (eds.), Lives of the English Martyrs. Second Series. The Martyrs declared Venerable (London, 1914), vol. i (1583-1588), pp. 114-126

F. H. Cheetham., ‘Eccleston church in Leyland’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vols 63 (1891 and 1892), pp. 201-232. Available online: https://www.hslc.org.uk/journal/vol-63-1911

Christopher Haigh, Reformation and Resistance in Tudor Lancashire (Cambridge, 1975)

‘The parish of Eccleston’, in A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 6, ed. William Farrer, J Brownbill (London, 1911), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol6/pp155-162 [accessed 19 February 2025]

‘Eccleston – Edgbaston’, in A Topographical Dictionary of England, ed. Samuel Lewis (London, 1848), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-dict/england/pp139-144 [accessed 19 February 2025]

Historic England:

Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Towngate (1362129)

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1362129 National Heritage List for England